It’s February of 2008. We are living our last few months in China before returning home to live in the USA. It’s now or never. We get our visa and book our flight to Burma – now known as Myanmar – for our Chinese New Year Holiday. Several days after beginning our journey, we arrive at the airport closest to Lake Inle, in the Southern Shan State of Myanmar. Our guide, Ko Zahn, greets us warmly and asks if we would like to see Pindaya Cave, which has one of the largest single collections of Buddhas in the world.

|  |

Only late in the afternoon do we realize that we are still quite far from our hotel. Moreover, in order to get to our hotel we have to cross a large lake, in a small boat.

|  |

We board the small boat and set out. I notice the houses in the villages along the way do not have glass in the windows, and the people appear to be washing clothing by hand in the lake.

Thinking of their washing clothes, made me think about my own grubby clothing and to be grateful I was staying someplace that had promised a hot shower.

As we traveled in the boat, everything got darker.

As darkness sets in, there are no lights anywhere on the lake. Our motorboat buzzes noisily through the darkness, guided by only dark shadows on the horizon where we once saw mountains and trees. The only light was from some stars and from the orange glow of small fires on the sides of mountains far away, marking the places were slash and burn agriculture was being practiced.

The darkness of the shadows on the horizon, the fact of being out on a lake at dusk, the vision of the occasional tiny spots of light, lake took me back to my childhood, in my mind. When I was very young, my parents lived in central Florida, in the days before it had so many people. While my father went to college and my mother taught school, we rented a house in the middle of an orange grove, on the shore of a large lake. My parents grew most of their own food. Every day, my Dad would put me in his little John Boat and take me out fishing for fish that we would have for supper that night.

We always tried to be home by dusk, but a few times we got caught out on the lake. Pitch black on a moonless night, there were only a few houses on the lake where an electric light might shine. My father would have to navigate any way he could to find the way back, guided by light from the moon, by the few electric lights on the lake, and by the dark shadows on the shore. Occasionally, he even navigated by the bullfrog-ish sound of the huge, male alligator that lived about 300 yards from our home and used to steal our chickens.

I would always worry whether my father would find the right shadows on that shore and not get lost. How would he know when the shadow would be our house and our dock? Somehow, though, he always did know.

Just like that childhood memory, I came to realize that there were also no electric lights shining on this lake. I knew our hotel had electricity, so when I could see no lights at all, I knew we still had a long way to go. Gradually, a small speck of light appeared and grew larger. “Our hotel, finally!” I thought to myself. But it was not. We passed that speck of light and went on further into the darkness.

Finally, another speck of light appeared on the horizon and then grew larger and larger. We arrived, tired, to a warm welcome at our hotel, a hot shower, and a hot dinner. I love this photo of a gecko I shot outside our room. Our electricity, powered by a generator, shut off promptly at 11:00 PM. It was so black after that time that I couldn’t locate the door handle to the bathroom door.

The next morning at daybreak, I went outside and this is what I saw:

It felt so cold. I was glad that I had brought jackets. I was grateful that I had hot water for a hot shower, instead of having to rely on a cold sponge bath from the lake, like the local people were doing.

Inle Lake is a unique and beautiful location. It is a relatively shallow, high altitude lake that is fed by seasonal rainfall. Centuries ago, people began living in houses built on stilts over the lake and constructing floating gardens by piling mud on top of water hyacinths. The topography is among the most beautiful I have ever seen. This is not why I shared this particular journal entry, however.

I wanted to give a feel for life without electricity. The feeling of being in utter darkness. A room so dark one cannot see the door knob.

We who have electricity, take it so much for granted. We think we can’t live without it. But, in fact, we can. The electric light bulb was not invented until 1879. For thousands of years before that time, in fact for all of time, humans lived without electricity. Eons of time. Even today, most of the world does live with far less of it than we Americans do.

It says something about electrical use in the USA when the entire continent of Africa uses less electricity than we use in our air conditioners alone.

Here, at Inle Lake, is an example of a different kind of life:

|  |

There are thousands of people who live here, in Myanmar, without electricity. No electric hot water. No light bulbs at night. No ovens.

They follow a traditional way of life that has been sustained for centuries and for generation upon generation. (The photos just below are from market day at a local market.)

| |

|

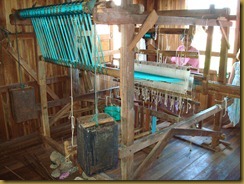

Our visit to Myanmar enabled us to glance a vision of life from before the industrial revolution, from a time before capitalism and mass production fueled by electricity had displaced more human-powered mechanisms. Here are people producing silk fabrics.

The Western media loves to demonize the Myanmar government. I am not writing a missive to justify the abuse of human rights. On the other hand, I think there is a part of the story that is not being told, as well. What if that government is, in fact, protecting a very important human value: a way of life that cannot compete with Wal Mart?

| We who have electricity need to consider that not having electricity or mass industrialization does not mean that life is unhappy or feels deprived. Do these children look deprived?  |  |

Perhaps the goal should not be purely to export, blindly, Western style capitalism to other countries, but instead to develop more of a balance. A sustainable lifestyle that is kind to the planet. Maybe we could give up a light bulb or two, and these children could have better access to antibiotics. And what we get is a more sustainable lifestyle that acknowledges we don’t need to keep getting more, more, more. What they get is to hang onto a way of life without the terrible risks associated with not having for instance good access to medical care.

What I’m saying is that we need to rethink our own values and priorities. Absolutely, I wish for every child born in Myanmar to have the same promise of life, health, and happiness as a child born in the USA. Absolutely, I would love for people everywhere to have hot, running water and electricity. How can we introduce these things without destroying the lifestyle that is already there?

How can we put an air conditioner in the beach house and still leave the windows open to catch the sea breeze? Are the two ideas mutually exclusive? If we open our windows now, are we forced to listen to an air conditioner instead of the ocean breezes? We must also not forget that returning to a simpler lifestyle was what the Khmer Rouge originally was all about. And then it was return Cambodia to ethnic Cambodians and to a simpler lifestyle. And then it was get rid of a certain ethnic group that brought too much capitalist influence. And then it was get rid of anyone who might have ever looked at me wrong.

These things can get over-simplistic and lead right to the slippery slope. So, I’m not going to make any generalizations or make any suggestions, other than to make one request: “Think about it.”

And now, for Lent, I’m going to pull this back into scripture. There is a vision of utopia in the Bible. A vision of a just world, where things are right and in balance and at peace. Ever since writing about the Fast of Isaiah Chapter 58, my mind has dwelt on the way that vision permeates visions of peace and justice in the Old Testament. It’s not just an individual, "me-me-me" peace. Rather, it’s a collective peace. It’s concerned very deeply with how we live in society and what our society does collectively for itself, with what we do for each other. This idea of being at peace must, almost by definition, includes creating a more sustainable and just economy and social system. Now, if only we can have the wisdom to know how to do that!

Technorati Tags: sustainability,capitalism,myanmar,inle lake,lake inle,Isaiah 58,fast of isaiah,traditional way of life,Burma

No comments:

Post a Comment

Thank you for your comment!